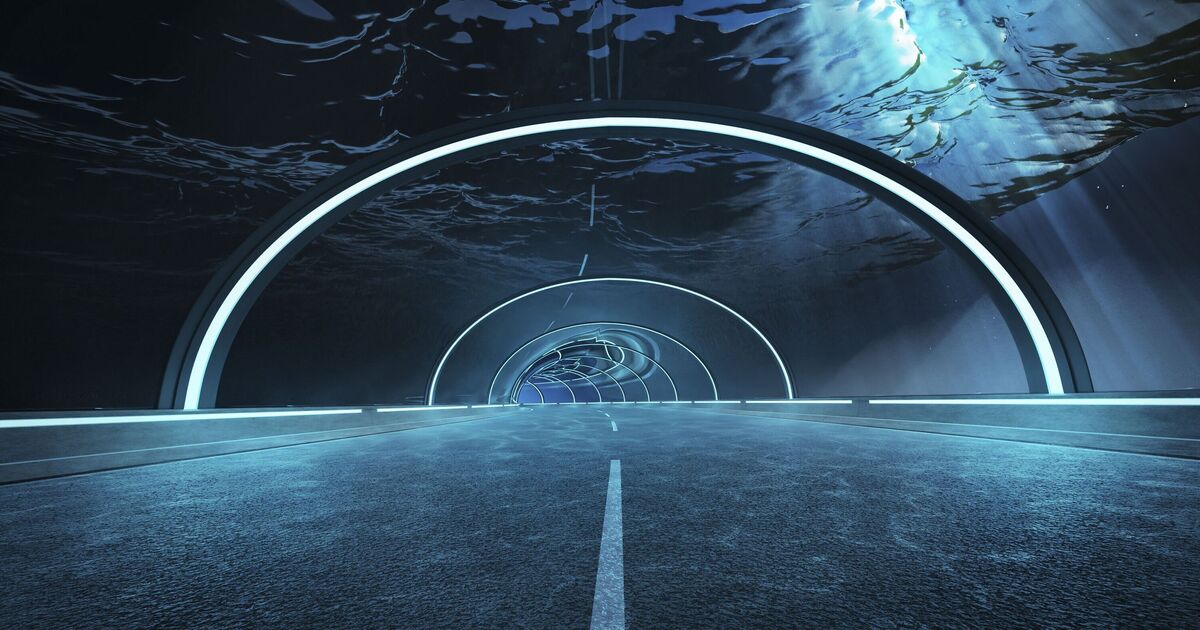

It’s an eager traveller’s dream – being able to hop on a train in Europe and emerge in Africa, all without stepping foot on a boat or plane. Tourists could be relaxing on the southern coast of Spain one minute and exploring the blue streets of Chefchaouen, in Morocco, the next.

In recent years, records have been broken time and again as the latest infrastructure megaproject is completed. But this ambitious project may just be the biggest and boldest yet. The Express spoke with construction expert Bill Bencker of Ace Avant Concrete Construction about how engineers would build a connection between Africa and Europe, and if it’s even possible.

“As a concrete contractor who has spent years working on massive infrastructure projects, I’ve seen firsthand what it takes to turn ambitious ideas into reality. And let me tell you – this one is as bold as they come,” said Mr Bencker.

“An underwater tunnel between Europe and Africa would be a historic engineering achievement, but it wouldn’t come easy.”

Before any plans can be put into action, the tunnel’s location must be chosen. According to Bencker, the most logical route would be across the Strait of Gibraltar – the narrow waterway separating Spain and Morocco.

At its narrowest point, the Strait is about 8.7 miles wide, which on paper does not seem too bad. The world’s longest tunnel, the Laerdal Tunnel, is currently found in western Norway. It stretches for 15.2 miles and takes about 20 minutes to pass through.

However, it would not be that simple. In some places, the water depth drops to over 3,000 feet, making it significantly more challenging than the Laerdal Tunnel, a road tunnel, and even the Channel Tunnel.

“Because of the deep waters, a typical bored tunnel beneath the seabed would be difficult,” explained Bencker. “Instead, engineers might consider a floating submerged tunnel, anchored to the seabed with cables, or a hybrid of an underground tunnel and an above-seabed structure.”

Next, we turn to construction time. Would we even be able to use this tunnel in our lifetime?

“If you think this could be built in a decade, think again,” revealed Bencker. “A project of this scale would likely take anywhere from 15 to 25 years from planning to completion.

“That’s not just because of the construction itself – the real time-eaters are the feasibility studies, environmental impact assessments, securing funding, and political agreements.

“Even if everyone agreed to start tomorrow, we’d be looking at years of geological surveys and experimental designs before the first bit of concrete is poured.”

For context, the Channel Tunnel required four years of studies and discussions before the procurement procedure was initiated in 1985.

“Then comes the actual construction, which would be slow and expensive, given the challenges of working underwater with extreme pressures and seismic activity.”

A big reason why a Europe-Africa tunnel has not been built yet, no matter how game-changing it would be, is the cost. According to Beckner, estimates put the cost somewhere between £42billion and £84billion, depending on the design. The far-simpler Channel Tunnel cost the modern equivalent of around £11.7billion.

“And with a project like this, overruns are almost guaranteed. Unexpected geological conditions, material costs, and political hold-ups could drive that number even higher,” the expert added. “So, before a single tunnel boring machine is switched on, we’re talking decades of negotiations just to figure out who’s going to pay for it.”

Then we come to the big question – is it even possible?

“From an engineering perspective, we have the technology to build a tunnel like this. Countries like Norway and China are already experimenting with submerged floating tunnels, and deep-sea construction is improving every year.

“But feasibility isn’t just about technology – it’s also about whether it makes sense politically and economically.

“Would there be enough demand to justify the cost? Likely yes – trade and tourism between Europe and Africa are already booming. But, there are also concerns about security, border control, and migration policies, which could slow down or even derail the project entirely.

“I’d say it’s possible, but we’re looking at a long, long road ahead. Between the cost, politics, and technical challenges, it’s going to take a massive push from [Spain and Morocco’s] governments and investors to make this a reality.”